中华蜜蜂(Apis cerana cerana)急造王台时子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂的父系分布

研究中华蜜蜂(Apis cerana cerana)蜂群急造王台过程中子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂的父系分布规律。

通过人工操作使4群(A~D)中华蜜蜂失去蜂王,蜂群利用本群幼虫急造王台,并采集子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂样本。采用微卫星简单重复序列(simple sequence repeats,SSR)分子标记和毛细管电泳技术检测样本基因型,使用MateSoft软件判定父系归属,并通过卡方检验分析父系分布规律。

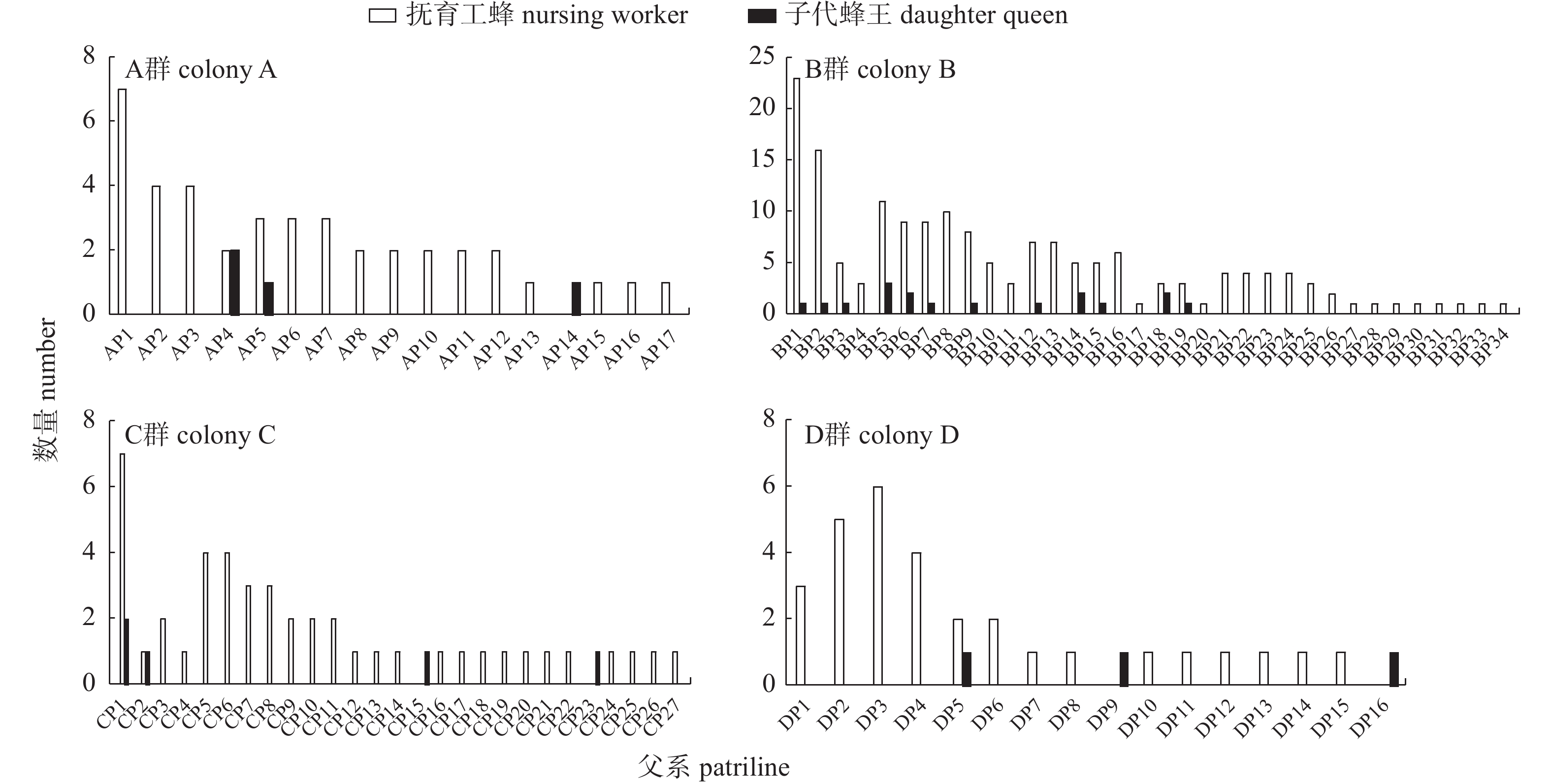

在4个试验群中,分别发现16~34个父系,各群产生的子代蜂王来自3~13个父系,占总父系数量的17.6%~38.2%;抚育工蜂几乎遍布所有父系,卡方检验结果显示:PWA群=0.945 6、PWB群=0.005 9、PWC群=0.145 4、PWD群=0.787 3;子代蜂王与其抚育工蜂之间的同一父系比例范围为0%~20%。

在中华蜜蜂蜂群急造王台过程中,子代蜂王主要来自少数父系,而抚育工蜂则几乎来源于所有父系。子代蜂王与其抚育工蜂之间未表现出显著的父系关联。

Patrilineal Distribution of Daughter Queens and Nursing Workers in Apis cerana cerana Colonies During Emergency Queen Rearing

To study the patrilineal distribution of daughter queens and their nursing workers in Apis cerana cerana colonies during emergency queen rearing.

Four A. cerana cerana colonies were dequeened through artificial manipulation. Samples of emergency daughter queens, reared from larvae of the original colony, and their nursing workers were collected. Genotypes of all samples were determined by microsatellite simple sequence repeats (SSR) molecular markers and capillary electrophoresis. The patrilineal origin of each sample was identified by MateSoft software, and the patrilineal distribution was analyzed through Chi-square tests.

In the four experimental colonies (A, B, C, D), 16-34 paternal lineages were identified respectively. The daughter queens of each colony emerged from only 3-13 patrilines, which accounted for 17.6%-38.2% of the total patrilineal diversity of each colony. Nursing workers were derived from nearly every patriline in all four colonies. Chi-square test results showed that: PW colony A=0.945 6, PW colony B=0.005 9, PW colony C=0.145 4, and PW colony D=0.787 3. Up to 20% of the daughter queens and their nursing workers belong to the same paternal line, but it could also be as low as 0%.

During emergency queen rearing in A. cerana cerana, daughter queens emerge from only a few patrilines, while nursing workers arise from almost all patrilines of the colony. There is no significant paternal relationship between the daughter queens and their nursing workers.

-

Keywords:

- Apis cerana cerana /

- daughter queen /

- nursing worker /

- patriline /

- microsatellite molecular markers

-

中华蜜蜂(Apis cerana cerana),简称为中蜂,是蜜蜂属(Apis)东方蜜蜂种下的1个重要亚种。其蜂群为基本生存单位,具有明显的“劳动分工”特征,体现了高度社会化的群居生活[1]。为了适应这一生存和繁殖方式,中华蜜蜂采用独特的多雄交尾机制[2]。1只中蜂蜂王通常会与6~27只雄蜂交尾[3],这种一雌多雄的交尾方式导致蜂群内出现多个不同父系。同母同父的后代属于同一父系,也称为全同胞姐妹,亲缘系数为0.75;同母异父的后代属于不同父系,为半同胞姐妹,亲缘系数为0.25。与单一或少数父系遗传结构相比,多个父系带来的遗传多样性更有利于蜜蜂群体的生存和发展[4-6]。例如:蜂群中不同父系的工蜂对温度的敏感阈值存在差异,当蜂巢内的温度升高到一定值时,并非所有工蜂同时开始调节温度,而是由特定父系的工蜂率先启动“煽风降温”机制,调节蜂巢内的温度[4],这有助于避免巢温剧烈波动,以维持蜂巢内温度的相对稳定。

蜂群中的不同父系个体之间也存在潜在的竞争。例如:当蜂群意外失王或蜂王出现病、老、伤、残等情况时,抚育工蜂必须尽快培育新的子代蜂王,否则整个蜂群将面临灭亡的威胁。由于资源(如食物、空间、抚育工蜂数量等)有限,且蜂群内存在多个父系,选择哪些幼虫培育为新的蜂王变得复杂。此时,抚育工蜂面临3种选择:第一是向亲选择[7-8],即培育与自己属于同一父系的全同胞姐妹幼虫为子代蜂王;第二是向优选择,即以蜂群整体利益为主,不考虑亲缘关系,选择质量最优的幼虫[9],通常选择3日龄内的小幼虫作为候选对象[10];第三是随机选择[11]。针对这一问题,前人以西方蜜蜂(A. mellifera)为材料进行了大量研究。部分研究结果表明:蜂群在培育子代蜂王时确实存在向亲选择的现象[7-8, 12-13];然而,另一些学者的研究结果则显示:抚育工蜂与子代蜂王之间并未表现出显著的同父系关系[14-16],故不支持蜂群育王过程中“向亲选择”的观点。最近的研究提出了“贵族父系”理论,认为蜂群中可能存在少数隐秘的贵族父系,这些父系的子代蜂王被选中的概率显著高于其他父系[17-18]。因此,目前关于蜜蜂育王过程中子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂的父系分布规律尚未形成一致的学术观点。

工蜂在抚育子代蜂王时的选择标准至关重要,它直接决定了蜂群的未来命运。这不仅是社群生物学研究的重要科学问题,其研究结果也将为蜜蜂育种技术的发展提供关键的理论基础。现有研究主要以西方蜜蜂为材料,采用微卫星分子标记分辨蜜蜂个体的父系归属。本研究以中国本土的中华蜜蜂为试验对象,采用急造王台时的人工育王方法采集子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂样本,并通过微卫星分子标记技术进行基因分析,以判定其父系归属。研究结果将为进一步揭示蜜蜂社群在育王过程中的子代蜂王选育规律提供有力的数据支持。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 样本采集

本研究于2019年6—8月在云南农业大学实验蜂场进行。使用4群中华蜜蜂(A、B、C、D),群势为5~6足脾,蜜粉充足。使用囚王笼将蜂王囚禁于边脾,18~24 h后将带有蜡质王台的育王框置于蜂箱中的脾位。4~5 h后,选取2日龄小幼虫并将其移入蜡质王台内,移虫完成后立即将育王框放回原群进行抚育。24 h后取出育王框,用镊子采集伸进王台内的抚育工蜂并浸于无水乙醇中备用,每个王台采集10只抚育工蜂,A、B、C、D群分别采集到抚育工蜂40、169、45、30只。72 h后,将封盖的王台转移至温度为(34.5±0.1) ℃、湿度为75%±5%的恒温培养箱中培育,A、B、C、D群共成功培育出子代蜂王4、17、5、3只。刚出房的处女蜂王与之前采集的抚育工蜂对应记录并浸于无水乙醇中备用。

1.2 DNA提取

采用天根生化科技有限公司提供的血液/细胞/组织基因组DNA提取试剂盒,对所有子代新蜂王及其对应的抚育工蜂样本进行全基因组DNA提取。

1.3 PCR扩增及产物分型

PCR引物为周丹银等[19]研究中的4个微卫星位点(表1),每对引物中的上游引物添加了6-Fam荧光标记,由生工生物工程(上海)股份有限公司合成。PCR反应体系包括:约40 ng/μL DNA模板2.0 μL,10 μmol/L上、下游引物各0.8 μL,5 U/μL Taq酶(Takara) 0.2 μL,2.5 mmol/L dNTP 1.6 μL,25 mmol/L MgCl2 1.2~1.6 μL,10×PCR缓冲液(不含Mg2+) 2.0 μL,加入超纯水补足至20.0 μL。PCR反应在避光条件下进行,扩增条件为:95 ℃预加热5 min,95 ℃变性1 min,68.6~70.5 ℃退火30 s,72 ℃延伸1 min,循环32次,最后72 ℃延伸5 min。PCR产物送至生工生物工程(上海)股份有限公司进行毛细管电泳分型。

表 1 引物信息Table 1. Primer information位点

loci引物序列 (5'→3')

primer sequences产物长度/bp

product length循环次数

number of

cycles退火温度/ ℃

annealing

temperature$c_{{\mathrm{Mg}}^{2+}} $/

(mmol·L−1)染色体位置

chromosome

locationNCBI登录号

NCBI

accession No.AC139 F:ACCAGTGTTCACGGTAAACG

R:GATCATAGAGTACGCGCAAAG330 32 68.6 2.0 Chr.4 AJ509681 AT113 F:GACCGAGACGAGCCAGTTTG

R:GCACCACGAGGTCTTCCGT176 32 70.5 1.5 Chr.2 AJ509559 AT163 F:CGCATTAGCATATACACGAGG

R:TCGGGTCTCGCAGTAACG140 32 70.5 1.5 Chr.11 AJ509601 AT170 F:GCAACAAATTACAAGTCTCCC

R:CTTAGTTAGGGCTTGCGTTC198 32 68.8 1.5 Chr.14 AJ509606 1.4 数据分析

使用GeneMapper 3.7软件对原始峰图进行解析并生成Excel格式数据,随后人工校对形成分析数据。利用MateSoft V1.0软件[20]推测母蜂王基因型,并根据母蜂王等位基因判定子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂的父系归属(当个体与母蜂王在某微卫星位点上的2个等位基因完全相同时,无法确定父系等位基因,MateSoft将按“最少父系数”原则进行分析)。通过SigmaPlot 14.0软件统计各试验群蜜蜂样本的父系分布情况并进行图示。以随机分布为零假设,使用R语言V4.0.5对父系分布数据进行卡方检验。

2. 结果与分析

从试验蜂群中探测到的父系数量分别为:A群17个、B群34个、C群27个、D群16个,符合前人研究[3]中记录的父系数量范围。

2.1 子代蜂王的父系分布

4个试验蜂群共成功培育出29只子代蜂王,其中A群4只、B群17只、C群5只、D群3只。由图1可知:所有试验群的子代蜂王均来自多个父系,并大致平均分布在这些父系之间。卡方检验结果显示:PQA群=0.778 8、PQB群=0.982 9、PQC群=0.896 4、PQD群=1.000 0,均呈现随机分布态势。然而,子代蜂王的父系仅占蜂群父系的部分。具体分布为:A群来自3个父系,占本群父系数量的17.6% (3/17);B群来自13个父系,占本群父系数量的38.2% (13/34);C群来自5个父系,占本群父系数量的18.5% (5/27);D群来自3个父系,占本群父系数量的18.8% (3/16)。

![]() 图 1 各试验群子代蜂王和抚育工蜂的父系分布注:A、B、C、D群父系按照顺序分别命名为AP1~AP17、BP1~BP34、CP1~CP27、DP1~DP16;下同。Figure 1. Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers of each colonyNote: The patrilineal distribution of colony A, B, C and D were named AP1-AP17, BP1-BP34, CP1-CP27 and DP1-DP16, respectively; the same as below.

图 1 各试验群子代蜂王和抚育工蜂的父系分布注:A、B、C、D群父系按照顺序分别命名为AP1~AP17、BP1~BP34、CP1~CP27、DP1~DP16;下同。Figure 1. Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers of each colonyNote: The patrilineal distribution of colony A, B, C and D were named AP1-AP17, BP1-BP34, CP1-CP27 and DP1-DP16, respectively; the same as below.2.2 抚育工蜂的父系分布

4个试验蜂群共采集到284只抚育工蜂,其中A群40只、B群169只、C群45只、D群30只。由图1可知:抚育工蜂几乎来自本群所有父系,但不同父系的分布频率存在差异。卡方检验结果显示:PWA群=0.945 6、PWB群=0.005 9、PWC群=0.145 4、PWD群=0.787 3,除B群外,其他群体均呈随机分布态势。

2.3 子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂的父系分布

对各试验群的子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂的父系分布数据进行了综合分析,结果(表2~5)显示:每只子代蜂王的10只(个别为9只)抚育工蜂中,最多2只(20%)、最少0只(0%)与其归属于同一父系。子代蜂王与其抚育工蜂之间未表现出显著的全同胞关系,更倾向于随机分布。

表 2 A群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布Table 2. Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony A父系

patrilineA1 A2 A3 A4 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 AP1 *** ** ** 17.50 AP2 ** ** 10.00 AP3 ** ** 10.00 AP4 ● * * 5.00 AP5 ** ● ●* 7.50 AP6 * * * 7.50 AP7 ** * 7.50 AP8 * * 5.00 AP9 * * 5.00 AP10 * * 5.00 AP11 * * 5.00 AP12 * * 5.00 AP13 * 2.50 AP14 ● 0.00 AP15 * 2.50 AP16 * 2.50 AP17 * 2.50 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 0.0 0.0 0.0 10.0 注:A、B、C、D群父系按照顺序分别命名为AP1~AP17、BP1~BP34、CP1~CP27、DP1~DP16,A、B、C、D群蜂王按照顺序分别命名为A1~A4、B1~B17、C1~C5、D1~D3;●表示子代新蜂王归属父系,*表示抚育工蜂归属父系,符号数量表示个体数量;Nwb表示本群父系抚育工蜂样本数,Nwc表示本群抚育工蜂样本数,Nwq表示与被抚育子代新蜂王属同一父系的抚育工蜂样本数,Nwz表示该子代新蜂王的抚育工蜂样本数;下同。

Note: The patrilineal distribution of colony A, B, C and D were named AP1-AP17, BP1-BP34, CP1-CP27 and DP1-DP16, respectively; all daughter queens of colony A, B, C and D were named A1-A4, B1-B17, C1-C5 and D1-D3, respectively; ● represents the patriline of daughter queens, * represents the patriline of nursing workers, and the number of symbols represents the number of individuals; Nwb represents the total sample number of nursing workers of the patriline, Nwc represents the total sample number of nursing workers in this colony, Nwq represents the number of nursing workers belonging to the same patriline as the daughter queen, Nwz represents the total number of nursing workers of the daughter queen; the same as below.表 3 B群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布Table 3. Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony B父 系

patrilineB1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B7 B8 B9 B10 B11 B12 B13 B14 B15 B16 B17 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 BP1 * *** * * ** * * ** ** ** *** *** * ● 13.60 BP2 * * * ** ●** * ** * * ** * * 9.46 BP3 * * * ● ** 2.96 BP4 * * * 1.78 BP5 ●** * *** * * * ● ** 6.51 BP6 * ● * ** * ** * * ● 5.33 BP7 ** ● * ** * * * * 5.33 BP8 * * * * * * * * * * 5.91 BP9 * * * ●* * * * * 4.73 BP10 ** * ** 2.96 BP11 ● * * 1.78 BP12 * ● ** * * ** 4.14 BP13 * *** * * * 4.14 BP14 ● ● ** * * * 2.96 BP15 ●* ** * * 2.96 BP16 * * * * * * 3.55 BP17 * 0.59 BP18 * * ●* ● 1.78 BP19 * * * ● 1.78 BP20 * 0.59 BP21 * * ** 2.37 BP22 * * * * 2.37 BP23 * ** * 2.37 BP24 * * ** 2.37 BP25 * * * 1.78 BP26 * * 1.18 BP27 * 0.59 BP28 * 0.59 BP29 * 0.59 BP30 * 0.59 BP31 * 0.59 BP32 * 0.59 BP33 * 0.59 BP34 * 0.59 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 10.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 表 4 C群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布Table 4. Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony C父系

patrilineC1 C2 C3 C4 C5 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 CP1 * ●* ●* *** * 15.56 CP2 * ● 2.22 CP3 ** 4.45 CP4 * 2.22 CP5 ** * * 8.89 CP6 * * ** 8.89 CP7 * * * 6.67 CP8 * * * 6.67 CP9 * * 4.45 CP10 * * 4.45 CP11 ** 4.45 CP12 * 2.22 CP13 * 2.22 CP14 * 2.22 CP15 0.00 CP16 ● * 2.22 CP17 * 2.22 CP18 * 2.22 CP19 * 2.22 CP20 * 2.22 CP21 * 2.22 CP22 * 2.22 CP23 ● 0.00 CP24 * 2.22 CP25 * 2.22 CP26 * 2.22 CP27 * 2.22 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 0.0 11.1 14.3 0.0 0.0 表 5 D群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布Table 5. Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony D父系

patrilineD1 D2 D3 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 DP1 * * * 10.00 DP2 ** * ** 16.67 DP3 *** *** 20.00 DP4 * *** 13.33 DP5 ●** 6.68 DP6 * * 6.68 DP7 * 3.33 DP8 * 3.33 DP9 ● 0.00 DP10 * 3.33 DP11 * 3.33 DP12 * 3.33 DP13 * 3.33 DP14 * 3.33 DP15 * 3.33 DP16 ● 0.00 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 0.0 20.0 0.0 3. 讨论

对于以社群为生存基本单位的社会性昆虫而言,蜂王(或蜂后)的质量直接关系到整个群体的命运。优质的蜂王(或蜂后)能够提高群体的群势,增强抗逆性和抗病性,从而提高群体的生存适应度[21]。在多父(母)系遗传背景下,哪些父(母)系的个体更可能被选为子代新王(后)?而抚育者又来自哪些父(母)系的成员?这是社群生物学中的重要科学问题。HALMITON提出的内涵适应度学说认为:社群性生物的利他主义行为旨在增加其基因在后代中的频率,因此,这种行为偏向于发生在亲缘关系较近的家庭成员之间[22]。根据这一理论,社群中负责抚育任务的成员应偏向于培养与自己有较高亲缘关系的全同胞个体成为子代新王,以扩大自身等位基因在群体中的出现频率,增加群体的内涵适应度,而在以蜜蜂[7-8, 12]、白蚁[23]等社会性昆虫为试验对象的研究中,确实发现了支持“向亲选择”理论的结果。研究者们还提出:昆虫几丁质外壳中的碳氢化合物可能是介导个体间识别亲疏远近的线索[24-25]。然而,随后逐渐有支持不同观点的研究结果出现。CHLINE等[15]使用西方蜜蜂进行试验时,发现抚育工蜂并不倾向于优先照顾同父系的子代蜂王;GOODISMAN等[26]则发现胡蜂(Vespula maculifrons)中不存在向亲选择;ZINCK等[27]也指出:蚂蚁(Ectatomma tuberculatum)工蚁在照顾蚁后时并未表现出向亲选择的行为。在本研究中,80%~100%的抚育工蜂与所抚育的子代蜂王归属于不同的父系,未表现出向亲选择的倾向,这一结果与前述研究[14-16]一致。

影响父系归属判定的因素主要包括以下3个方面。(1)数据样本量。1个王台从被选定到封盖前,平均接受约2 000次抚育照顾[28],包括饲喂、清理、温控等,参与抚育的工蜂超过百只(群势不同,数量有差异)。试验中采集的抚育工蜂样本有限,过度捕捉会显著减少王台的抚育照顾,进而影响子代蜂王的成活率,这可能导致某些父系未被采样,进而影响研究结果的代表性。(2)父系判定的技术和方法。早期研究使用等位酶[29-30]、腹部背板颜色[31-33]等作为父系标记,精确度较低;随着分子生物学技术的发展,微卫星标记已广泛用于父系鉴定[34-36],提高了精确度,但仍然存在长度趋同性[37]、无效等位基因等问题,可能导致父系误判。(3)实验设计与操作。蜂群在分蜂、新老蜂王交替或母蜂王意外死亡等情况下都会建立王台并培育子代蜂王,此时,蜂群所面临的生存条件(如温度、食物、群势等)差异较大,可能会影响蜂群选择子代蜂王的标准和原则。因此,模拟蜂群分蜂的实验设计[31, 36]和模拟母蜂王发生意外的实验设计[8, 38]可能得出不同的结论。此外,在自然状态下,蜂群育王通常在蜂巢内黑暗且稳定的巢温条件下进行,而在试验中,为了获取抚育工蜂的行为数据,育王过程往往暴露于可见光和外界温度下[16, 36, 39],这可能对抚育工蜂的行为产生影响。一些实验设计采用人工移虫提供幼虫[12, 14, 16, 40],这限制了子代蜂王的候选父系;而另一些实验则采用工蜂自然改造的王台[13, 17-18],进而导致父系归属判定产生差异。

一些学者提出蜜蜂可能遵循“向优选择”原则培育子代蜂王,因为选择压力要求蜂群中的蜂王必须足够优秀,需选出品质优良的卵或小幼虫培育为子代蜂王,这一特性可能是进化赋予蜜蜂的生物学特点。尽管目前尚缺乏直接证据支持这一观点,但前人的研究结果表明:子代蜂王通常只来源于少数几个父系[17-18, 21],因此,有学者提出蜂群中可能存在隐秘的贵族父系,这一现象被用来支持“向优选择”理论。该理论与本研究所发现的规律一致。此外,部分学者认为抚育工蜂的选择标准更多是基于食物和营养,而非通过遗传因素判断幼虫的优良程度,因此,获得更多营养的幼虫可能更容易被培育为子代蜂王[9]。目前关于“向优选择”理论仍存在诸多未解的问题,包括:(1)蜂群对“优良”标准的具体定义;(2)抚育工蜂如何感知并判断卵或幼虫是否优良。

综上所述,关于蜂群在多父系遗传背景下如何选择子代蜂王,仍是亟待进一步研究的科学问题。今后的研究应在实验技术上进行改进,以实现在不干扰子代蜂王培育过程的前提下,观察并记录工蜂的抚育行为,同时扩大抚育工蜂样本的采集量。理论上,所有参与抚育子代蜂王的工蜂都应当进行观察记录,并获取其父系归属数据。然而,现有的实验技术或是在记录观察过程中干扰了蜂群的正常秩序,或是进行破坏性采样,导致样本个体的后续抚育行为无法被观察记录。开发一种能够有效解决这些问题的技术方法,将对相关研究的深入突破起到至关重要的作用。

4. 结论

在中华蜜蜂蜂群急造王台的过程中,子代蜂王主要来源于蜂群中的少数父系,而抚育工蜂则几乎遍布于所有父系。子代蜂王与其对应的抚育工蜂之间未表现出显著的同父系关系。

-

图 1 各试验群子代蜂王和抚育工蜂的父系分布

注:A、B、C、D群父系按照顺序分别命名为AP1~AP17、BP1~BP34、CP1~CP27、DP1~DP16;下同。

Figure 1. Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers of each colony

Note: The patrilineal distribution of colony A, B, C and D were named AP1-AP17, BP1-BP34, CP1-CP27 and DP1-DP16, respectively; the same as below.

表 1 引物信息

Table 1 Primer information

位点

loci引物序列 (5'→3')

primer sequences产物长度/bp

product length循环次数

number of

cycles退火温度/ ℃

annealing

temperature$c_{{\mathrm{Mg}}^{2+}} $/

(mmol·L−1)染色体位置

chromosome

locationNCBI登录号

NCBI

accession No.AC139 F:ACCAGTGTTCACGGTAAACG

R:GATCATAGAGTACGCGCAAAG330 32 68.6 2.0 Chr.4 AJ509681 AT113 F:GACCGAGACGAGCCAGTTTG

R:GCACCACGAGGTCTTCCGT176 32 70.5 1.5 Chr.2 AJ509559 AT163 F:CGCATTAGCATATACACGAGG

R:TCGGGTCTCGCAGTAACG140 32 70.5 1.5 Chr.11 AJ509601 AT170 F:GCAACAAATTACAAGTCTCCC

R:CTTAGTTAGGGCTTGCGTTC198 32 68.8 1.5 Chr.14 AJ509606 表 2 A群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布

Table 2 Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony A

父系

patrilineA1 A2 A3 A4 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 AP1 *** ** ** 17.50 AP2 ** ** 10.00 AP3 ** ** 10.00 AP4 ● * * 5.00 AP5 ** ● ●* 7.50 AP6 * * * 7.50 AP7 ** * 7.50 AP8 * * 5.00 AP9 * * 5.00 AP10 * * 5.00 AP11 * * 5.00 AP12 * * 5.00 AP13 * 2.50 AP14 ● 0.00 AP15 * 2.50 AP16 * 2.50 AP17 * 2.50 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 0.0 0.0 0.0 10.0 注:A、B、C、D群父系按照顺序分别命名为AP1~AP17、BP1~BP34、CP1~CP27、DP1~DP16,A、B、C、D群蜂王按照顺序分别命名为A1~A4、B1~B17、C1~C5、D1~D3;●表示子代新蜂王归属父系,*表示抚育工蜂归属父系,符号数量表示个体数量;Nwb表示本群父系抚育工蜂样本数,Nwc表示本群抚育工蜂样本数,Nwq表示与被抚育子代新蜂王属同一父系的抚育工蜂样本数,Nwz表示该子代新蜂王的抚育工蜂样本数;下同。

Note: The patrilineal distribution of colony A, B, C and D were named AP1-AP17, BP1-BP34, CP1-CP27 and DP1-DP16, respectively; all daughter queens of colony A, B, C and D were named A1-A4, B1-B17, C1-C5 and D1-D3, respectively; ● represents the patriline of daughter queens, * represents the patriline of nursing workers, and the number of symbols represents the number of individuals; Nwb represents the total sample number of nursing workers of the patriline, Nwc represents the total sample number of nursing workers in this colony, Nwq represents the number of nursing workers belonging to the same patriline as the daughter queen, Nwz represents the total number of nursing workers of the daughter queen; the same as below.表 3 B群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布

Table 3 Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony B

父 系

patrilineB1 B2 B3 B4 B5 B6 B7 B8 B9 B10 B11 B12 B13 B14 B15 B16 B17 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 BP1 * *** * * ** * * ** ** ** *** *** * ● 13.60 BP2 * * * ** ●** * ** * * ** * * 9.46 BP3 * * * ● ** 2.96 BP4 * * * 1.78 BP5 ●** * *** * * * ● ** 6.51 BP6 * ● * ** * ** * * ● 5.33 BP7 ** ● * ** * * * * 5.33 BP8 * * * * * * * * * * 5.91 BP9 * * * ●* * * * * 4.73 BP10 ** * ** 2.96 BP11 ● * * 1.78 BP12 * ● ** * * ** 4.14 BP13 * *** * * * 4.14 BP14 ● ● ** * * * 2.96 BP15 ●* ** * * 2.96 BP16 * * * * * * 3.55 BP17 * 0.59 BP18 * * ●* ● 1.78 BP19 * * * ● 1.78 BP20 * 0.59 BP21 * * ** 2.37 BP22 * * * * 2.37 BP23 * ** * 2.37 BP24 * * ** 2.37 BP25 * * * 1.78 BP26 * * 1.18 BP27 * 0.59 BP28 * 0.59 BP29 * 0.59 BP30 * 0.59 BP31 * 0.59 BP32 * 0.59 BP33 * 0.59 BP34 * 0.59 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 10.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 表 4 C群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布

Table 4 Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony C

父系

patrilineC1 C2 C3 C4 C5 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 CP1 * ●* ●* *** * 15.56 CP2 * ● 2.22 CP3 ** 4.45 CP4 * 2.22 CP5 ** * * 8.89 CP6 * * ** 8.89 CP7 * * * 6.67 CP8 * * * 6.67 CP9 * * 4.45 CP10 * * 4.45 CP11 ** 4.45 CP12 * 2.22 CP13 * 2.22 CP14 * 2.22 CP15 0.00 CP16 ● * 2.22 CP17 * 2.22 CP18 * 2.22 CP19 * 2.22 CP20 * 2.22 CP21 * 2.22 CP22 * 2.22 CP23 ● 0.00 CP24 * 2.22 CP25 * 2.22 CP26 * 2.22 CP27 * 2.22 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 0.0 11.1 14.3 0.0 0.0 表 5 D群子代蜂王及其抚育工蜂分布

Table 5 Patrilineal distribution of all daughter queens and their nursing workers in colony D

父系

patrilineD1 D2 D3 (Nwb/Nwc)×100 DP1 * * * 10.00 DP2 ** * ** 16.67 DP3 *** *** 20.00 DP4 * *** 13.33 DP5 ●** 6.68 DP6 * * 6.68 DP7 * 3.33 DP8 * 3.33 DP9 ● 0.00 DP10 * 3.33 DP11 * 3.33 DP12 * 3.33 DP13 * 3.33 DP14 * 3.33 DP15 * 3.33 DP16 ● 0.00 (Nwq/Nwz)×100 0.0 20.0 0.0 -

[1] 曾志将. 养蜂学[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2017. [2] PALMER K A, OLDROYD B P. Evolution of multiple mating in the genus Apis[J]. Apidologie, 2000, 31(2): 235. DOI: 10.1051/apido:2000119.

[3] OLDROYD B P, CLIFTON M J, KERRIE P, et al. Evolution of mating behavior in the genus Apis and an estimate of mating frequency in Apis cerana (Hymenoptera: Apidae)[J]. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 1998, 91(5): 700. DOI: 10.1093/aesa/91.5.700.

[4] JONES J C, MARY R M, SONIA G, et al. Honey bee nest thermoregulation: diversity promotes stability[J]. Science, 2004, 305(5682): 402. DOI: 10.1126/science.1096340.

[5] HEATHER R M, KELLY M B, THOMAS D S. Genetic diversity within honeybee colonies increases signal production by waggle-dancing foragers[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B (Biological Sciences), 2008, 275(5): 809. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1620.

[6] ECKHOLM B J, HUANG M H, ANDERSON K E, et al. Honey bee (Apis mellifera) intracolonial genetic diversity influences worker nutritional status[J]. Apidologie, 2014, 46(2): 1. DOI: 10.1007/s13592-014-0311-4.

[7] PAGE R E, ERICKSON E H. Selective rearing of queens by worker honey bees: kin or nestmate recognition[J]. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 1984, 77(5): 578. DOI: 10.1093/aesa/77.5.578.

[8] PAGE R E, ROBINSON G E, FONDRK M K. Genetic specialists, kin recognition and nepotism in honey-bee colonies[J]. Nature, 1989, 338(13): 576. DOI: 10.1038/338576a0.

[9] SAGILI R R, METZ B N, LUCAS H M, et al. Honey bees consider larval nutritional status rather than genetic relatedness when selecting larvae for emergency queen rearing[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8(1): 7679. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-25976-7.

[10] SHI Y Y, HUANG Z Y, ZENG Z J, et al. Diet and cell size both affect queen-worker differentiation through DNA methylation in honey bees (Apis mellifera, Apidae)[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(4): e18808. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018808.

[11] LATTORFF H M, MORITZ R F. Context dependent bias in honeybee queen selection: swarm versus emergency queens[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2016, 70(8): 1411. DOI: 10.1007/s00265-016-2151-x.

[12] VISSCHER P K. Kinship discrimination in queen rearing by honey bees (Apis mellifera)[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1986, 18(6): 453. DOI: 10.1007/BF00300521.

[13] OSBORNE K E, OLDROYD B P. Possible causes of reproductive dominance during emergency queen rearing by honeybees[J]. Animal Behaviour, 1999, 58(2): 267. DOI: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1139.

[14] WOYCIECHOWSKI M. Do honey bee, Apis mellifera L., workers favour sibling eggs and larvae in queen rearing[J]. Animal Behaviour, 1990, 39(6): 1220. DOI: 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80798-5.

[15] CHLINE N, ARNOLD G. A scientific note on the lack of nepotism in queen larval feeding during emergency queen rearing in a naturally mated honey bee colony[J]. Apidologie, 2005, 36(1): 141. DOI: 10.1051/apido:2005001.

[16] KOYAMA S, HARANO K I, HIROTA T, et al. Rearing of candidate queens by honeybee, Apis mellifera, workers (Hymenoptera: Apidae) is independent of genetic relatedness[J]. Applied Entomology & Zoology, 2007, 42(4): 541. DOI: 10.1303/aez.2007.541.

[17] MORITZ R F A, LATTORFF H M G, NEUMANN P, et al. Rare royal families in honeybees, Apis mellifera[J]. Naturwissenschaften, 2005, 92(10): 488. DOI: 10.1007/s00114-005-0025-6.

[18] WITHROW J M, TARPY D R. Cryptic “royal” subfamilies in honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(7): e0199124. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199124.

[19] 周丹银, 刘意秋, 龚雪阳, 等. 青藏高原地区东方蜜蜂遗传多样性分析[J]. 江西农业大学学报, 2019, 41(3): 565. DOI: 10.13836/j.jjau.2019066. [20] MOILANEN A, SUNDSTRM L, PEDERSEN J S. MATESOFT: a program for deducing parental genotypes and estimating mating system statistics in haplodiploid species[J]. Molecular Ecology Notes, 2004, 4(4): 795. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00779.x.

[21] TARPY D R, SIMONE-FINSTROM M, LINKSVAYER T A. Honey bee colonies regulate queen reproductive traits by controlling which queens survive to adulthood[J]. Insectes Sociaux, 2016, 63(3): 169. DOI: 10.1007/s00040-015-0452-0.

[22] HAMILTON W D. The evolution of altruistic behavior[J]. The American Naturalist, 1963, 97(5): 354. DOI: 10.1086/497114.

[23] MINTTUMAARIA H, LISELOTTE S. Worker nepotism among polygynous ants[J]. Nature, 2003, 421(8): 910. DOI: 10.1038/421910a.

[24] PAGE R E, METCALF R A, METCALF R L, et al. Extractable hydrocarbons and kin recognition in honeybee (Apis mellifera L.)[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 1991, 17(4): 745. DOI: 10.1007/BF00994197.

[25] ARNOLD G, QUENET B, CORNUET J M, et al. Kin recognition in honeybees[J]. Nature, 1996, 379(8): 498. DOI: 10.1038/379498a0.

[26] GOODISMAN M A D, KOVACS J L, HOFFMAN E A. Lack of conflict during queen production in the social wasp Vespula maculifrons[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2007, 16(12): 2589. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03316.x.

[27] ZINCK L, CHÂLINE N, JAISSON P. Absence of nepotism in worker-queen care in polygynous colonies of the ant Ectatomma tuberculatum[J]. Journal of Insect Behavior, 2009, 22(3): 196. DOI: 10.1007/s10905-008-9165-9.

[28] HUANG Z Y, OTIS G W. Inspection and feeding of larvae by worker honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae): effect of starvation and food quantity[J]. Journal of Insect Behavior, 1991, 4(3): 305. DOI: 10.1007/BF01048280.

[29] PAGE R E, METCALF R A. Multiple mating, sperm utilization, and social evolution[J]. The American Naturalist, 1982, 119(2): 263. DOI: 10.1086/283907.

[30] PAGE R E, ROBINSON G, E. Reproductive competition in queenless honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera L.)[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1994, 35(2): 99. DOI: 10.1007/BF00171499.

[31] GETZ W M, BRÜCKNER D, PARISIAN T R. Kin structure and the swarming behavior of the honey bee Apis mellifera[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1982, 10(4): 265. DOI: 10.1007/BF00302815.

[32] GETZ W M, SMITH K B. Genetic kin recognition: honey bees discriminate between full and half sisters[J]. Nature, 1983, 302(10): 147. DOI: 10.1038/302147a0.

[33] HOGENDOORN K, VELTHUIS H H W. Influence of multiple mating on kin recognition by worker honeybees[J]. Naturwissenschaften, 1988, 75(8): 412. DOI: 10.1007/BF00377820.

[34] ESTOUP A, SOLIGNAC M, CORNUET J M. Precise assessment of the number of patrilines and of genetic relatedness in honeybee colonies[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B (Biological Sciences), 1994, 258(1351): 1. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0133.

[35] TILLEY C A, OLDROYD B P. Unequal subfamily proportions among honey bee queen and worker brood[J]. Animal Behaviour, 1997, 54(6): 1483. DOI: 10.1006/anbe.1997.0546.

[36] CHLINE N, MARTIN S J, RATNIEKS F L W. Absence of nepotism toward imprisoned young queens during swarming in the honey bee[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 2005, 16(2): 403. DOI: 10.1093/beheco/ari003.

[37] ESTOUP A, TAILLIEZ C, CORNUET J M, et al. Size homoplasy and mutational processes of interrupted microsatellites in two bee species, Apis mellifera and Bombus terrestris (Apidae)[J]. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 1995, 12(6): 1074. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040282.

[38] CHALINE N, ARNOLD G, PAPIN C, et al. Patriline differences in emergency queen rearing in the honey bee, Apis mellifera[J]. Insectes Sociaux, 2003, 50(3): 234. DOI: 10.1007/s00040-003-0664-6.

[39] SCHNEIDER S S, DEGRANDI-HOFFMAN G. The influence of worker behavior and paternity on the development and emergence of honey bee queens[J]. Insectes Sociaux, 2002, 49(4): 306. DOI: 10.1007/PL00012653.

[40] PAGE R E, ERICKSON E H. Kin recognition and virgin queen acceptance by worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.)[J]. Animal Behaviour, 1986, 34(4): 1061. DOI: 10.1016/S0003-3472(86)80165-8.

下载:

下载: